Afrobeats Has Not Given Back (Yet)

Streamlining the African Music Industry’s Export-Led Model

By Bomi Fagbemi

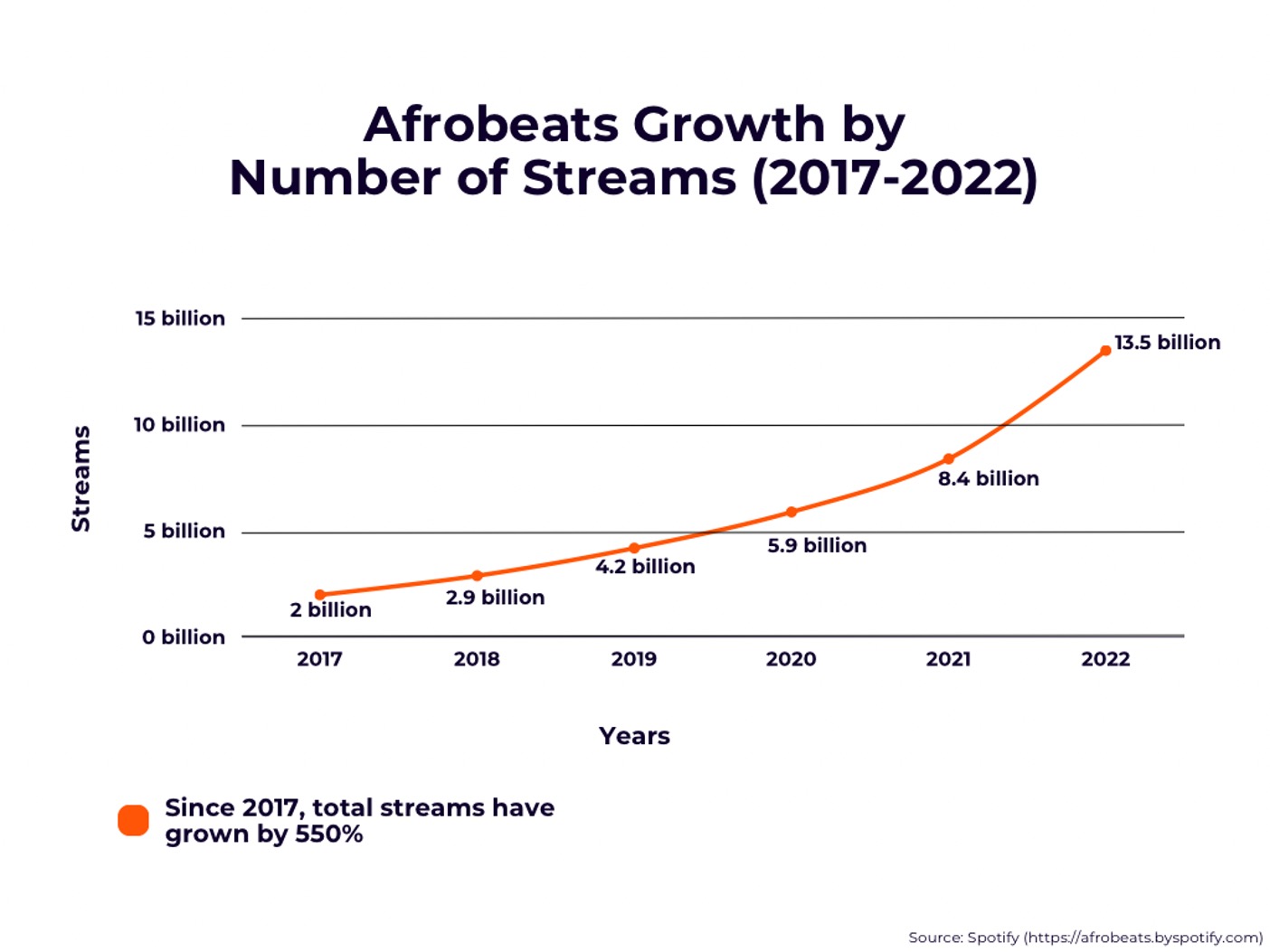

Over the past 36 months, Afrobeats artists have hit unprecedented heights globally. Rema’s Calm Down is one of the world’s biggest songs, Davido was on the flagship singles for the 2022 World Cup, and Essence was a global ‘song of the summer’ in 2021. This explosion of interest has culminated in the Recording Academy creating a new “Best African Music Performance” category for the Grammys. Despite this success and near omnipresence, the emergence of afrobeats has papered over the cracks of an incomplete creative ecosystem—one that lacks the necessary institutions to properly recognise and celebrate its own greatest proponents. Beyond continental pride gained from being the frontrunners of the genre, Afrobeats has not yet given back to the Nigerian populace in any meaningful way.

Singer Davido who was on the flagship single for the 2022 World Cup. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

AFROBEATS — WHAT’S IN A NAME?

For brevity’s sake, ‘afrobeats’ is the name that was given to music from Africa to explain it to Western ears. It is not so much a genre as a catch-all term for the popular music coming out of West Africa in a particular period. As much as Nollywood is a lazy christening by foreign media, afrobeats as a term is best viewed as useful for export.

Afrobeats was coined in the UK in the early 2010s, as West African artists started to break through into popular consciousness thanks to the internet and diaspora. Music blogs flourished online, and the increased democratization of music-making led to an explosion of artists releasing music constantly. The term should not mean anything to the average Nigerian. Naira Marley and his electric Marlians movement, Tems and her soulful R&B, all get lumped into the same category as Mavin Records’ newest class of private equity-backed teenage pop stars. Some artists like Burna Boy prefer Afro-fusion or Afro-pop to avoid conflation with Fela’s Afrobeat. However, there is power in numbers, and labels tend to stick. Being under a unified umbrella allows artists to benefit from easier music discovery and curation, helping to attract new listeners and fans to the region.

The attitude surrounding afrobeats from its inception as a name, has been to package a slice of culture for export to the Western world. This is reinforced every time you hear an awkward addition to that remix your favourite song didn’t need. By and large, those that control the capital necessary to propagate afrobeats do not live in Nigeria. Afrobeats’ explosion is a genuinely encouraging sign of the quality we can produce and of the world being ready to listen to African voices. Despite all this present acclaim, though, the future of afrobeats feels more uncertain.

It may feel like there is an unending stream of musical talent in the country, but we cannot realistically support our biggest artists within our local market. Soon, the sounds may be familiar but the faces might change and we will be discussing afrobeats in the past tense. The current export-driven model of afrobeats is great for the artists that can benefit. However, maintaining ownership of the sound and ensuring the proceeds can directly benefit Nigerians would go a long way toward ensuring that independent artists can earn a living while remaining in their home markets.

Policy Recommendations

Education and Skill Development: Investing in education and skill development programs is crucial for nurturing talent and empowering future generations of creatives. Integrating music and arts education into school curricula, establishing performing arts academies and offering vocational training programs in music production, event management and related fields will equip aspiring artists and industry professionals with the necessary skills for success. For example, Nigeria can collaborate with existing educational institutions and music industry stakeholders to develop specialized music programs and training initiatives.

Tourism and Cultural Exchanges: Afrobeats can be a powerful tool for promoting tourism and cultural exchanges. Policymakers should collaborate with tourism boards and cultural agencies to develop marketing campaigns that showcase the vibrant music scene and cultural heritage of Africa. Organizing domestic and international music festivals, concerts, and cultural events will attract visitors and facilitate cultural exchange, generating economic benefits and promoting a positive image of the continent. A successful example is Ghana’s “Year of Return” campaign, which capitalized on the country’s rich cultural heritage to attract the African diaspora and boost tourism.

AFROBEATS’ COLLECTIVE OWNERSHIP

Afrobeats is currently another common thread that connects the Black diaspora. From Guineans in Coventry to Parisians from Mali, there’s a wide range of what is considered afrobeats. But who is supposed to build the institutions that recognize the achievements in the genre? Who are the authorities that ensure this cultural asset is managed correctly? Afrobeats in its current guise does not tell the story of Francophone and Lusophone artists who have amassed loyal fan bases across Europe and South America. It does not tell the stories of Kenyan Gengetone, Soukous in DR Congo, Kizomba in Angola and Cape Verde, or Mbalax in Senegal.

The artists who have reached global audiences are those who have benefited from international infrastructure. It’s no surprise that many artists happen to thrive outside the continent due to colonial linkages that foster a common language across populations, and stronger creative ecosystems. Asa & Nneka are examples of artists who had critical acclaim in Europe in the 2000s and have drawn influence from this latest wave of afrobeats ubiquity to drive resurgences in their career.

INCOMPLETE CREATIVE ECOSYSTEMS AND GETTING CHECKS

Artists do not make the most money from their music, record labels typically do. Recently, the channel has reopened for major labels in the US to sign Nigerian artists to publishing and distribution deals. The capital from these deals is essential, as the process of making and promoting music can be prohibitively expensive. Many artists struggle to find the funding they need for their projects, but the deals on offer are heavily skewed to favour the label. A record deal is essentially an advance payment for a specified body of work that must be recouped by the label before the artist is paid—they are essentially glorified loans, especially if artists cannot take advantage of the add-on services that labels can provide.

Policy Recommendations

Music Export Offices: Several European countries, such as the UK, Germany, and France, have established music export offices to support their music industries in expanding their reach globally. These offices provide resources, networking opportunities, and market development assistance to artists and music industry professionals. African countries can consider establishing similar offices to support the internationalization of their music industries, including Afrobeats.

Tax Incentives for Music Production: Some countries in the EU and the US offer tax incentives or rebates for music production and related activities. These incentives attract investment in music production, stimulate job creation, and contribute to the growth of the creative economy. African policymakers can explore implementing similar tax incentives to attract local and international investments in the Afrobeats industry.

Musician Ayra Starr is ranked the 9th Afrobeats artist of all time globally by Spotify, based on data gathered from their user base. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

The typical pop artist makes the bulk (typically over 50%) of their revenue from touring and live shows. The release cycle is typically geared towards an artist touring and connecting with their fanbase wherever they may be. There is no touring infrastructure in Nigeria and there is also a lack of dedicated music venues. So, there is no clear trajectory for a young, independent artist to earn a living that doesn’t involve international virality. We have huge cities with no public spaces or venues with the capacity to house the talent we’re generating. An artist like Wizkid, selling out arenas like the O2 in London (capacity >20k) for 3 consecutive nights, should not be doing shows in hotel conference rooms in his home city. The implication of this is that artists are best served catering to the audience with the most purchasing power.

Policy Recommendations

Infrastructure: To fully harness the potential of Afrobeats, policymakers should focus on developing a comprehensive and supportive creative ecosystem. This includes investing in infrastructure such as dedicated music venues, recording studios, and performance spaces, particularly in major cities. Establishing cultural institutions and performing arts academies that nurture and develop talent will further enhance the industry’s growth and sustainability.

Private-Public Partnerships: In cities like Austin, Texas (US), public-private partnerships have been instrumental in developing and maintaining music venues. The Austin City Council collaborated with private organizations to establish the Austin Music Venue Preservation Fund, which provides financial assistance to local music venues to help them weather the challenges of rising costs and gentrification. African policymakers can explore similar partnerships to support the creation and sustainability of music venues, ensuring there are dedicated spaces for performances and fostering a vibrant live music scene.

Research: To fully understand and harness the potential of the Afrobeats industry and the wider creative ecosystem, it is essential for policymakers to prioritize funding for academic research and data collection. By supporting academic institutions and researchers, governments can generate valuable insights into the dynamics, challenges, and opportunities within the creative sector. This can be achieved by establishing research grants and scholarships, fostering collaborative partnerships between academic institutions and industry stakeholders, and investing in data collection initiatives. By supporting these initiatives, policymakers can gain a comprehensive understanding of the industry, inform evidence-based policies, attract investment, and showcase the cultural and economic significance of Afrobeats. This knowledge-driven approach will enable the industry to thrive, foster innovation, and create an enabling environment for sustainable growth.

CONCLUSION: WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE

Afrobeats has undoubtedly reached impressive heights globally, but it is essential to ensure that its success translates into tangible benefits for Nigeria and the African continent. By implementing policies that focus on education and skill development, promoting tourism and cultural exchanges, offering tax incentives and grants to creative individuals and organizations, and developing infrastructure and music venues, policymakers can create a thriving creative ecosystem that supports artists, fosters economic growth, and maximizes the potential of Afrobeats. Furthermore, it is crucial for governments to recognize the immense potential of Afrobeats artists as image shapers. When artists like Burna Boy perform at iconic venues like Madison Square Garden, they have the power to transcend the realm of entertainment and become representatives of their respective countries. These artists can redirect global conversations away from narratives of insecurity and chaos, instead focusing on the extraordinary talent and creativity that Africans possess. However, for this approach to be effective, governments must proactively identify their international image-shaping objectives and strategically deploy these artists to contribute to those objectives. By harnessing the cultural diplomacy aspect of Afrobeats, governments can elevate their nation’s reputation and create a positive narrative that extends beyond the realm of music. Through these efforts, Afrobeats can become a catalyst for societal and economic transformation, ultimately empowering independent artists to earn a living while remaining in their home markets.

Bomi Fagbemi is a creative entrepreneur based in Lagos, Nigeria. He has spent time building digital communities with gelbsy, The Republic and KANAAL. His current interests lie in completing African creative ecosystems and sustainable food production.

This article is part of The Africa Center’s Policy Positions series. The recurring publications will engage with the policy and governance dimensions of noteworthy stories coming out of Africa. Please follow @theafricacenter on Twitter, Instagram, and LinkedIn for updates on new posts.